Introduction: The Hidden Money Game

There is a financial system running quietly in the background of your life.

Think of it like an invisible operating system for money. Wealthy people know how it works. They use it every day. Most regular workers don’t even know it exists.

You weren’t taught this in school. You weren’t really meant to use it. In fact, most people are pushed toward a completely different money game.

But once you see how this system works, you can’t unsee it.

This chapter will walk you through the basic “owner’s playbook” — the way wealthy people structure their money, especially using real estate and the tax code, so their wealth grows faster than the government can tax it.

1. Two Games: Workers vs. Owners

There are basically two kinds of players in the money game:

- Workers – People who earn a paycheck from a job.

- Owners – People who own things that make money (businesses, stocks, real estate, etc.).

Both groups live in the same country, use the same currency, and pay the same government.

But they do not play by the same rules.

How the Tax Code Is Actually Designed

Here’s what most people never learn:

- The tax code (the giant rule book about taxes) is not mainly designed for workers.

- It is designed to reward owners.

If you’re a worker, you earn a salary, and the government taxes that salary before almost anything else.

If you’re an owner, especially of certain kinds of assets, the rules are very different. You can:

- Use deductions and write‑offs

- Delay taxes into the future

- Borrow against your wealth tax‑free

- Sometimes pass huge amounts of money to your children with little or no tax on the gains

The moment you cross the line from worker to owner — even with something as simple as one rental property — you start playing a different game.

This book is about that game.

2. Why Real Estate Is the Everyday Doorway

Wealthy families often use:

- Businesses

- Stocks

- Real estate

All three can plug into the owner’s playbook.

But if you’re a normal person without millions of dollars in stocks or a giant company, there’s one especially powerful and accessible path:

Real estate.

Real estate has four big advantages you don’t get from a normal paycheck:

- Cash Flow – Rent money left over after expenses.

- Leverage – You can use a small amount of your money and a big bank loan to buy something expensive.

- Appreciation – The property can go up in value over time.

- Tax Advantages – The government gives special tax breaks to real estate owners.

And one of those breaks is something called depreciation.

What Is Depreciation?

Depreciation is the government pretending your property is “wearing out” over time, even if it’s brand new and looks perfect.

Because of this, the IRS lets you:

- Deduct a portion of the property’s value from your income each year

- Lower your taxable income on paper

- Pay less in taxes, even if in real life the property is going up in value

So a simple rental property can:

- Pay you money each month (cash flow)

- Become more valuable over time (appreciation)

- Help you save on taxes (depreciation)

That’s already powerful. But it becomes much more powerful when you change how you think about selling and borrowing.

3. The Usual Mindset: Sell and “Cash Out”

Let’s walk through a simple example.

Step A: Buying the House

Imagine you buy a single‑family home for $400,000.

- You put $80,000 down (20% down payment).

- You borrow $320,000 from the bank (a mortgage).

- You rent it out, and after all expenses, you make about $300 a month in cash flow.

Behind the scenes:

- You’re taking depreciation each year, which lowers your taxable income.

- Over time, the house rises in value. Let’s say after a few years it’s now worth $500,000.

You’ve “gained” $100,000 in value on paper.

Step B: What Most People Do

Most people think:

“Wow, I made $100,000! I should sell and take the profit.”

So they sell the property for $500,000.

- They pay off the remaining mortgage.

- They walk away with their original money plus the $100,000 profit.

But then the government knocks.

That $100,000 “profit” is called a capital gain.

Depending on your income:

- You might pay around 15–20% in capital gains tax.

- So your $100,000 turns into $80,000–$85,000 after taxes.

You feel good about the profit… but now:

- You no longer own the house.

- You no longer get the monthly cash flow.

- You no longer get appreciation or depreciation from that property.

You scored some points, but then you hit a reset button on your wealth journey.

Every time you sell like this, you reset.

You give the government a cut and start over from scratch.

That is the worker mindset applied to an asset:

- earn → get taxed → spend what’s left → repeat.

Wealthy people try to avoid that reset.

4. The Owner’s Mindset: Borrow, Don’t Sell

Wealthy people understand a core rule:

Selling = Taxes. Borrowing ≠ Income.

And money that isn’t income is usually not taxed.

Let’s go back to the same house.

The Same House, The Owner’s Way

- Original purchase price: $400,000

- Original loan: $320,000

- Over time, your tenants have paid the mortgage down to, say, $280,000.

- The house is now worth $500,000.

You have something called equity:

Equity = Property value – Loan balance

Equity = $500,000 – $280,000 = $220,000

That $220,000 is wealth that belongs to you.

Now here’s the key move.

Instead of selling, an owner asks:

“How much can I borrow against this property?”

Most banks will lend up to about 75% of the property’s value in a refinance.

- 75% of $500,000 = $375,000

You already owe $280,000, so if you refinance:

- New loan: $375,000

- Old loan paid off: $280,000

- Cash to you: $95,000

You just put $95,000 of tax‑free cash into your pocket.

Why is it tax‑free?

Because:

- It’s not considered income.

- It’s considered debt (you’re borrowing it).

- The IRS does not tax borrowed money.

You still:

- Own the house

- Collect rent

- Benefit from future appreciation

- Keep using depreciation

You now also have $95,000 to use as a down payment on another property.

This is the owner’s mindset:

Don’t sell the asset that feeds you.

Use that asset to help you buy more assets.

Yes, it uses debt. But for owners:

- Debt is a tool, not automatically a danger.

- As long as your assets (like rentals) pay for the debt, it can be very powerful.

- What they truly fear is not debt. They fear taxable events like big sales.

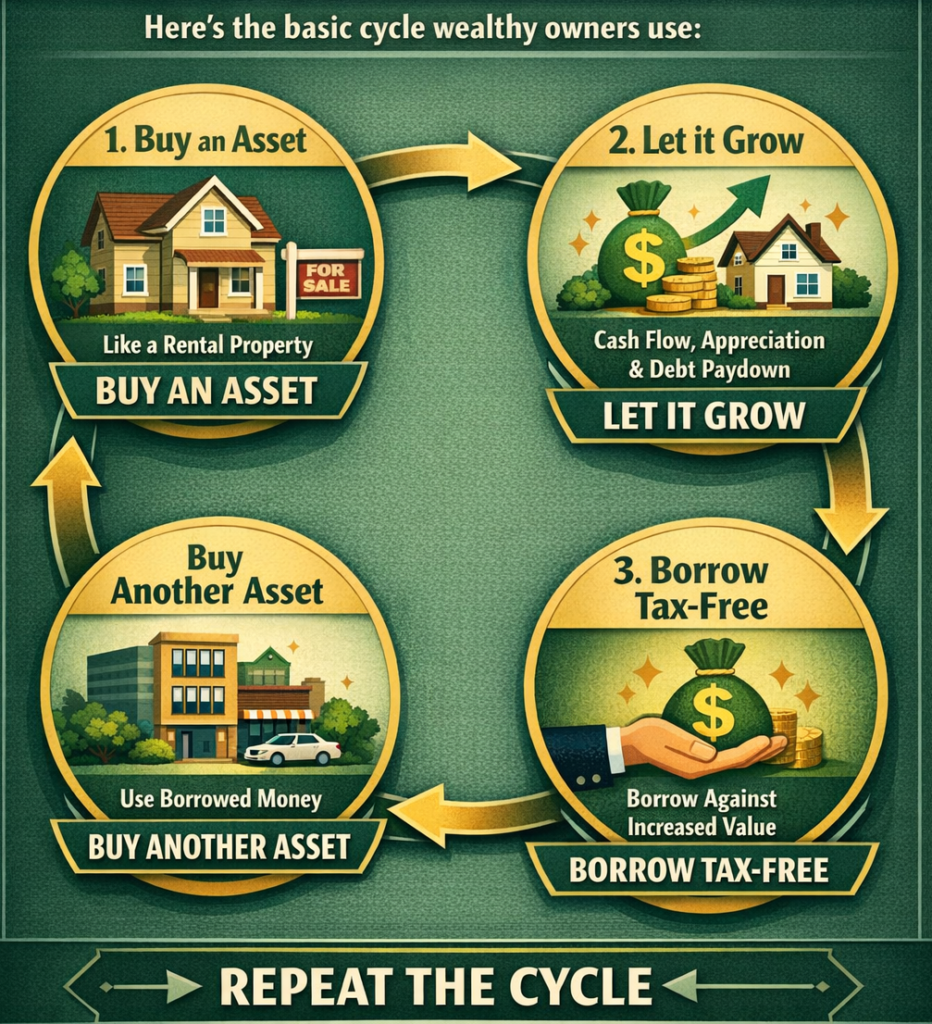

5. “Borrow Until You Die”: The Wealth Cycle

Here’s the basic cycle wealthy owners use:

- Buy an asset (like a rental property).

- Let it grow (cash flow + appreciation + debt paydown).

- Borrow against its increased value, tax‑free.

- Use that borrowed money to buy another asset.

- Repeat.

Over time they build a portfolio (a collection) of assets that:

- Pay them regular income

- Grow in value

- Offer valuable tax deductions

- Can be borrowed against over and over

This is called “borrow until you die.”

How Billionaires Use the Same Idea

Billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk are famous for taking a $1 salary.

Why?

- They don’t need a paycheck.

- They own billions of dollars in stock in their companies.

- If they sold that stock, they would owe massive taxes.

- Instead, they borrow against their stock.

Their stock acts like the house in our example:

- It’s an asset that has value.

- Banks are willing to lend against it.

- Borrowing does not trigger income tax.

So they borrow against their stock and use that money to:

- Live

- Invest

- Grow their companies

All while keeping their taxable income extremely low.

What Happens When They Die?

This is where it gets even more wild.

When someone dies and leaves assets (like stocks or real estate) to their heirs, in many cases those assets get something called a “step up in basis.”

Very simply:

- The government resets the “purchase price” of the asset to its value at the date of death.

- If the heirs sell the asset right away, they might owe little to no tax on all the gains that happened during the previous owner’s life.

So:

- The original owner enjoyed borrowing against the asset for decades.

- They often paid very little tax during that time.

- When they die, their kids get the asset almost as if they bought it at today’s price.

- The huge increase in value over time can escape taxation.

This is totally legal. The system was designed this way.

It allows wealth to stay in families and keep compounding across generations — while most workers are taxed heavily every year.

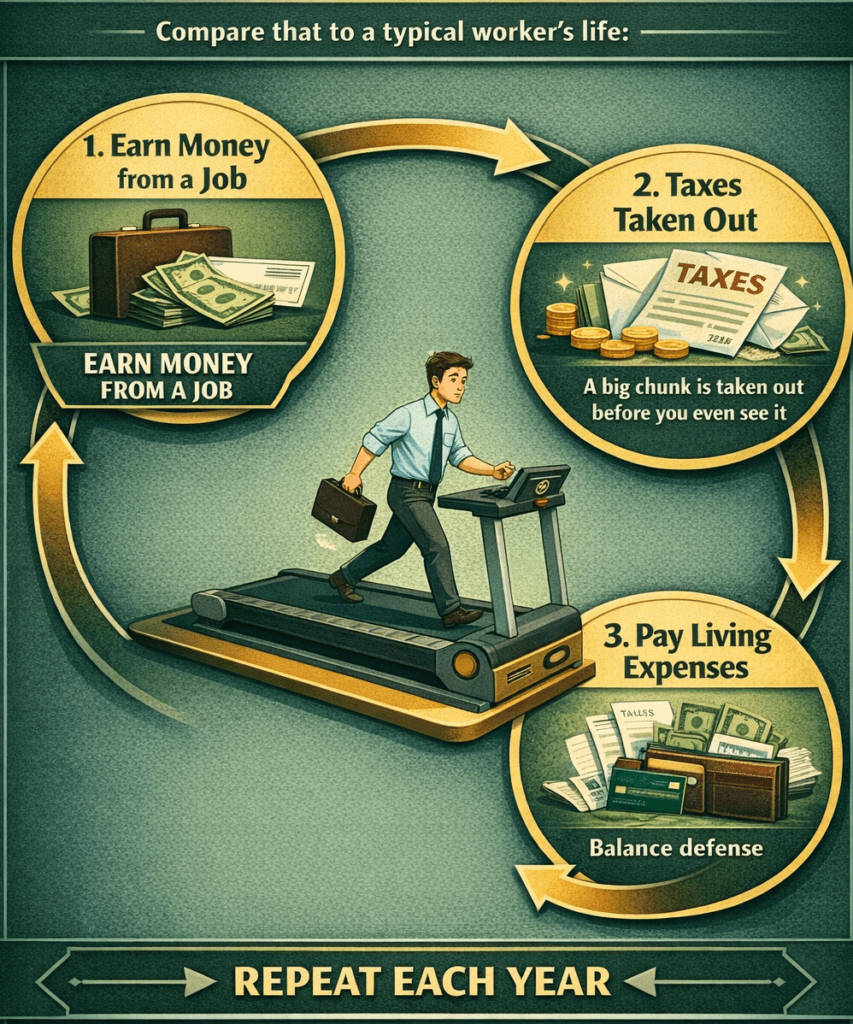

6. The Worker Treadmill

Compare that to a typical worker’s life:

- You earn money from a job.

- A big chunk is taken out for taxes before you even see it.

- You spend what’s left on living expenses.

- Repeat each year.

For many People (Mostly Americans):

- You’re effectively working 3–4 months per year just to cover your tax bill.

Year after year, this makes it hard to build serious capital (a big chunk of money) that you can invest.

The difference between the two paths:

- Isn’t how smart you are.

- Isn’t how hard you work.

It’s about access:

- Access to information

- Access to strategies

- Access to assets that the tax code favors

The good news: You don’t need to be a billionaire with stocks in a giant company.

Real estate — especially short‑term rentals — can give everyday people a path into this game.

7. The Tax Twist: Short‑Term Rentals (Airbnbs)

So far we’ve talked about regular rentals, where tenants stay for months or years.

There’s another category: short‑term rentals (STRs), like many Airbnb or VRBO properties, where guests usually stay for a few days or weeks.

The IRS treats these differently from long‑term rentals if:

- You materially participate in managing them — in simple words, you’re actively involved, and it’s like a real business you run.

Material Participation (In Simple Terms)

To be considered as “materially participating,” you might:

- Spend at least 100 hours a year working on the property

- And do more work than any other individual or company working on it (like cleaners, managers, etc.)

This can include:

- Dealing with guests

- Handling bookings

- Managing cleaners and repairs

- Setting prices, listing details, and so on

Why does this matter?

Because if you materially participate in a short‑term rental, it can move from being a “passive” investment to an active business in the eyes of the tax code.

And that changes everything.

8. Depreciation and Bonus Depreciation

You already know:

- Depreciation = a yearly tax deduction that assumes your property is wearing out.

Normally, a rental property’s building value is depreciated slowly over many years (for some property types, as long as 39 years).

But there’s a special rule called:

Bonus depreciation

Bonus depreciation lets you take a huge chunk of those future depreciation deductions up front, in the first year.

Instead of:

“Here’s a little tax break each year for decades,”

it’s more like:

“Here, take a massive tax break right now.”

This can create huge paper losses in the first year — even if the property is making money in real life.

For short‑term rentals where you materially participate, those paper losses can be used to offset your W‑2 income (your day‑job paycheck).

That’s the twist.

9. Example: Turning Your Tax Bill Into Your First Investments

Let’s put the pieces together with numbers.

Step A: The Worker’s Starting Point

Imagine:

- You work a normal job.

- You earn $100,000 in W‑2 income (a salary).

- You might owe roughly $18,000–$22,000 in federal income taxes for the year (exact number depends on your situation, but this is a reasonable estimate).

Normally:

- That $18k–$22k goes straight to the government.

- You never see it.

- You can’t use it to build wealth.

Step 2: Buying a Short‑Term Rental

Now suppose you buy a $500,000 short‑term rental property and:

- You actively manage it (you materially participate).

- You get a cost segregation study done (a detailed analysis that breaks the property into parts with different depreciation speeds, which boosts bonus depreciation).

With bonus depreciation plus cost segregation, a rough rule of thumb is:

- You might be able to take about 25% of the property’s value as a depreciation deduction in year 1.

For a $500,000 property:

- 25% of $500,000 = $125,000

So, on paper, the property shows a $125,000 loss in year 1.

Remember: This is mostly a paper loss created by depreciation. The property might still be making real money.

Step B: Offsetting Your Job Income

Because you materially participate and it’s a short‑term rental, that $125,000 loss can be used to:

- Offset your $100,000 of W‑2 income from your job.

So:

- Taxable income from job: $100,000

- Minus rental loss: $125,000

- New taxable income: effectively $0 for the year

Your expected tax bill of $18k–$22k?

- Wiped out for that year.

- You’ve “kicked the can down the road” on those taxes.

You still have $25,000 of extra loss left ($125,000 loss – $100,000 income).

You can carry that forward into the next year to reduce your taxes again.

Step 4: What Do You Do With the Saved Taxes?

Instead of sending $18,000–$22,000 to the IRS, you now keep that money.

Plus, ideally:

- Your short‑term rental is also making cash flow from guests staying there.

Now, you might:

- Use the tax money you kept + the cash flow from the property

- As a down payment or renovation budget for another asset

Maybe that’s a second short‑term rental.

Step 5: Doing It Again

If you buy a second short‑term rental and:

- You again materially participate

- You again use bonus depreciation and cost segregation

Then:

- You can generate more paper losses

- Use them to offset more W‑2 income (or carry them forward)

- Keep more of each paycheck

- Redirect that money into more assets

This is how you start your own version of the borrow until you die strategy.

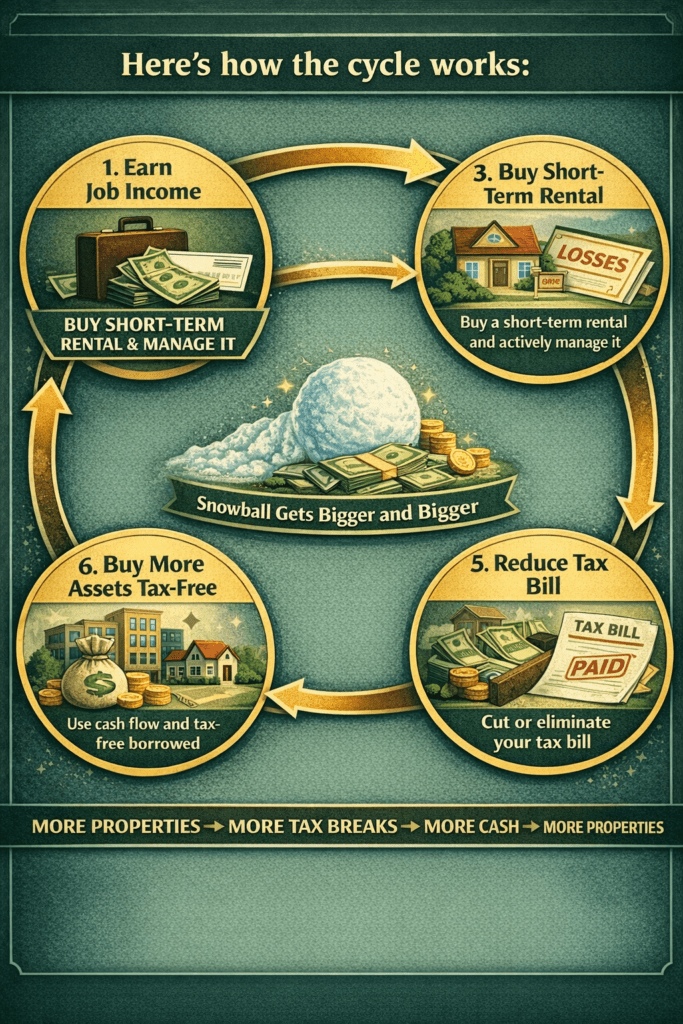

10. The Zero‑Tax Snowball

Let’s connect everything into one engine — the zero‑tax snowball.

Here’s how the cycle works:

- You earn income from your job (W‑2 income).

- You buy a short‑term rental and actively manage it.

- You use bonus depreciation to create large paper losses.

- Those losses offset your job income, cutting or eliminating your tax bill for the year.

- The money you would have paid in taxes stays in your hands.

- You use that money (plus rental cash flow) as down payments on more properties.

- Each new property:

- Produces cash flow

- Gains equity as loans are paid down and values rise

- Gives you more depreciation and deductions

- As your equity grows, you borrow against your properties (tax‑free) instead of selling.

- You use those borrowed funds to buy even more assets.

So the loop is:

- Cash flow grows equity

- Equity allows you to borrow tax‑free

- Borrowed money buys more assets

- More assets create more deductions (especially with bonus depreciation)

- More deductions reduce or eliminate taxes

- Lower taxes leave you with more capital to reinvest

The snowball gets bigger and bigger:

More properties → more tax breaks → more cash → more properties.

This is the engine many wealthy people use — just with much larger numbers.

11. What This Means for You

Here’s what you should take away from this post:

- The rich are not just “lucky.”

They are using a different set of rules that the system openly provides for owners. - Real estate is a realistic entry point.

You don’t need billions in stock. Even one rental, especially a short‑term rental you actively manage, can plug you into these rules. - Debt, used carefully, can be a powerful tool.

Wealthy people don’t panic at the word “debt.” They panic at the word “taxable.” They structure things so their assets pay for the debt. - Taxes are your biggest expense.

For many people, taxes cost more than food, housing, or anything else. Learning how the tax code works for owners is one of the highest‑leverage skills you can build. - The game is legal and intentional.

These aren’t “loopholes” in the sense of mistakes. The laws were written to encourage ownership, investment, and long‑term capital building.

Important Note

- Tax laws are complex and change over time.

- This blog post is a simplified explanation meant to help you understand the big picture.

- Before trying any real strategy like this in real life, anyone should talk to a qualified tax professional and financial advisor.

If you remember nothing else, remember this:

Workers earn, get taxed, and start over.

Owners buy assets, avoid selling, borrow against growing equity, and let the system multiply their wealth — often while paying surprisingly little in tax.

Seeing that difference is the first step to choosing which game you want to play.